by Daniel Edmiston

Seventy years ago, the National Assistance Act was passed as the final piece of the legislative jigsaw that saw the establishment of the UK welfare state. In 1958, amidst growing concern and criticism that ‘welfare’ was becoming a costly endeavour of principal benefit to the working classes, Richard Titmuss, in his seminal book, Essays on the Welfare State, demonstrated that we are all, to varying degrees, ‘welfare dependent’. To do so, he drew a distinction between ‘public’, ‘fiscal’ and ‘occupational’ welfare.

According to Titmuss, ‘public’ welfare can be understood as the conventional public services and social assistance (including direct payments) that comprise the welfare state. ‘Fiscal’ welfare is made up of the tax incentives, reliefs and allowances that encourage particular behaviours or outcomes amongst citizens. Beyond an employee’s salary, ‘occupational’ welfare includes subsidized payments, benefits and services in-kind, schemes, reliefs and pensions that are delivered through employers. Titmuss observed that the latter two forms tended to disproportionately benefit those in the middle and upper classes. Through such an exercise, he illustrated how particular forms and recipients of state assistance are often ignored and overlooked in social policy debates in ways that obscure the regressive potential of public social spending, particularly when it comes to occupational and fiscal welfare.

Since then, a great deal of research has also come to highlight the regressive operation of public welfare activity. For example, access to and quality of education and health services is often positively correlated with the capital(s) of social citizens (see Tudor Hart, 1971 and Matthews and Hastings, 2013). However, the social divisions of public welfare fostered through social security have received much less recognition. Where distributional analysis of the tax-benefit interface has been undertaken, it has tended to characterize regressive tendencies as the result of ‘benefit cuts for the poor’ and ‘tax cuts for the rich’. However, the reality is often much more complex with little visibility and understanding of what social security the middle and upper classes receive in mainstream political and media coverage.

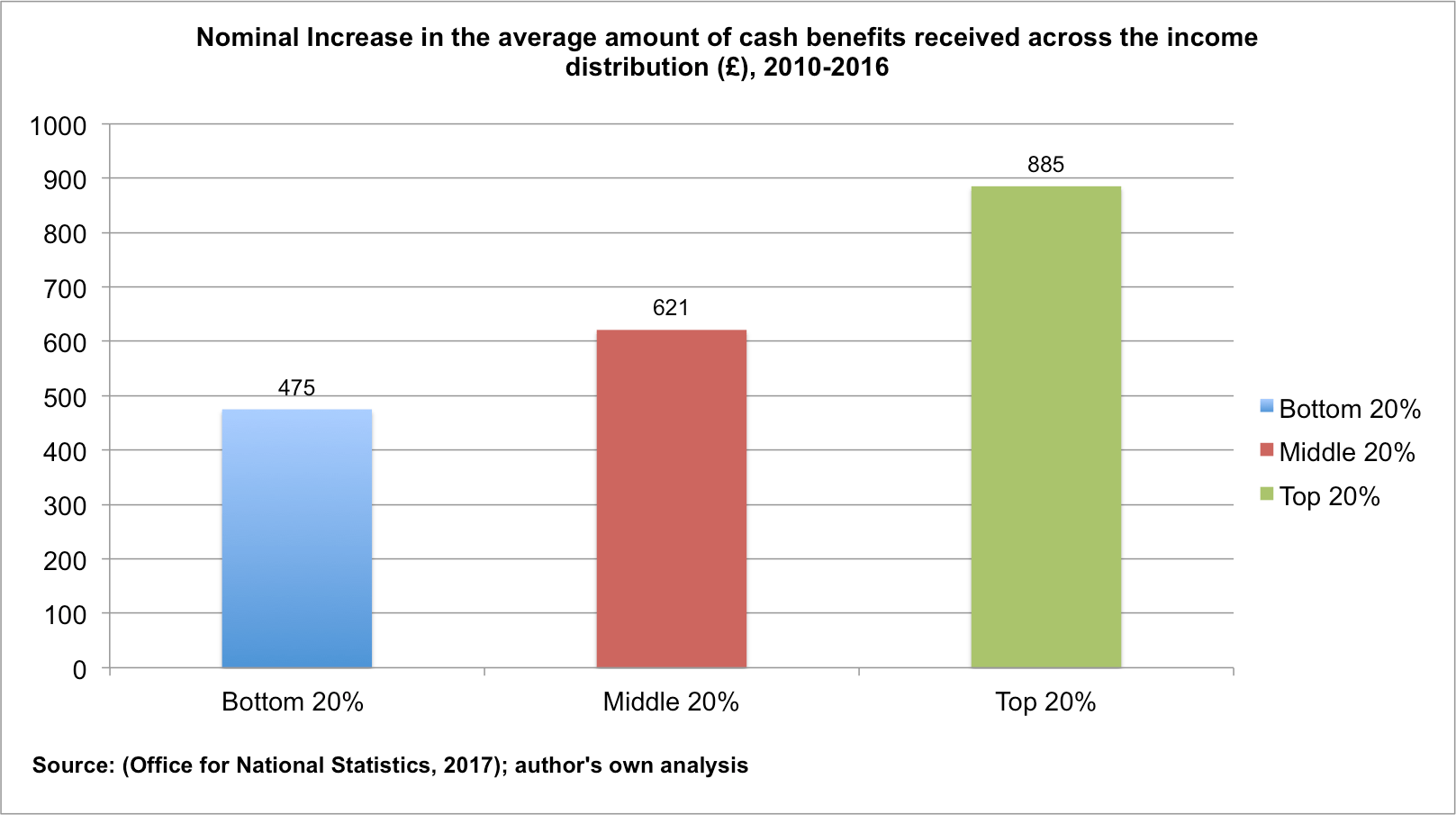

Over the last 40 years, there have been dramatic shifts in the amount of direct cash benefits received across the income distribution. Titmuss argued that lower socio-economic groups tend to be the primary beneficiaries of public welfare. However, long-term shifts mean there is now a shrinking difference in the amount of direct cash benefits received by those at the bottom and in the middle of the income distribution. Despite significant increases in their original income, households at the top of the income distribution have enjoyed a relative consolidation in the amounts they receive through direct cash benefits.

These emerging social divisions in the take-up and receipt of social security are driven by three key factors: differing rates of participation in the paid labour market; the changing quality and remuneration of work across the age and income distribution; and shifts in entitlement and take-up of social security across the life course.

Perhaps most importantly though, these shifts represent a political choice — about how we choose to spend public finances and where we direct them. This is significant for two reasons.

First, the specious notion that some are ‘contributing towards’ and some are ‘taking from’ the welfare state breeds resentment amongst the general public who are largely misinformed about public social spending and social security. Recent trends challenge on-going misconceptions about the welfare myth of ‘them’ and ‘us’ and demonstrate the need to broaden collective understandings of ‘welfare’.

Second, criticism of cuts to social security has tended to resort to a principle of human need to defend welfare entitlements. This has been regularly met with claims that there is no ‘Magic Money Tree’ — that we cannot afford such provisions because we have to live within our means. According to this logic, cuts to public social spending have had to be made in order to restore economic productivity and fiscal balance. However, changes in the distributional profile of social security demonstrate that austerity is a politically selective choice imposed on some and not others.

Since 2010, the average amount of money received in direct cash benefits has increased by £475 for households in the bottom 20 per cent of the income distribution, by £621 for those in the middle 20 per cent and by £885 for those at the top. This means that the average amount of cash benefits received by each of the income groups has increased by 7, 10 and 44 per cent, respectively. This amounts to real-term cuts to social security for those at the bottom and real-term increases for those at the top.

Such trends highlight the need to invoke a principle of not only need but also fairness in determining who receives what and why through the welfare state. More recent shifts in the social divisions of public welfare have disproportionately disadvantaged children, women, disabled people, Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic groups, and working-age people. This is not just the result of cuts to low-income social security; it is the result of political and policy decisions to safeguard and in certain instances increase middle-income and high-income social security. These two trends are intimately linked and it seems more sensible to talk about welfare recalibration rather than ‘cuts’ in this instance.

So, what research and policy agenda does this set? In light of the current state of play in UK welfare politics, it seems necessary to reinvigorate Titmuss’s approach and remind the general public once more that we are all welfare-dependent.

Recent calls to ‘look up’ in social policy research are more important than ever in this respect. Doing so can reveal inconsistencies in ‘Magic Money Tree’ thinking — particularly regarding the logic and implementation of welfare austerity and prevailing ideas about the functions and limits of welfare. Not only this but attention to who receives what and why can raise difficult but necessary questions about the reforms needed to move towards a UK welfare system that operates according to principles of both need and fairness.

Daniel Edmiston is a Lecturer in Sociology and Social Policy at the University of Leeds. His first book, Welfare, Inequality and Social Citizenship, is now available through Policy Press. He Tweets @daniel_edmiston.

Be the first to comment